The first time I expressed interest in comics, having read Sandman and not sure where to go next, there was a chorus of recommendations that amounted to “read Watchmen.” I read it, and found myself decidedly unimpressed and uninspired. Fearful of expressing such an opinion, however, given that this seemed to be a universally lauded work and part of the generally agreed upon comics canon, I kept that to myself.

Fast forward several years to now, where I have read a fair amount of comics across imprints and houses (primarily Marvel and Image, but a little bit of sampling the others as well) coupled with extensive reading of secondary sources and the small and largely disappointing field of comics scholarship, I now feel relatively confident in saying that I still don’t like Watchmen, but now I understand why.

I don’t like Watchmen because I’ve been reading comics in a post-Watchmen universe.

When Alan Moore wrote Watchmen, it was responding to a particular moment in time, both in history and in comics. The unfortunate thing since Watchmen’s publication, however, is that the premise has been removed from its original context and stretched to expand into a general philosophy of comics and storytelling. Shorthand for this philosophy is the portmanteau “grimdark”: a term that generally is used to mean stories that wallow in misery or “gritty realism” – here meaning a fixation on violence (frequently sexual) and a seeming inability of anyone to be happy. In a grimdark world, there is no such thing as heroes, morals are a mark of the weak, and women die in droves. “Grimdark” fiction purports to show the world in its unvarnished state, but more often than not what it really shows is a reality distorted through a cynical and limited lens that substitutes shock value for good storytelling.

Cynicism has its place, and I’m not saying everything needs to be sunshine and roses all the time. But there is such a thing as too far, and too much, and the one note storytelling that infected comics in the wake of Watchmen was it. When that’s the comics environment you’re familiar with, Watchmen doesn’t feel like something new or revolutionary: it feels like more of the same.

Moore wrote Watchmen with a specific aim: examining contemporary political anxieties (as in his other work, most obviously in V for Vendetta) and deconstructing the idea of the superhero. Moore said that Watchmen was about”power and about the idea of the superman manifest within society”, and critic Bradford Wright describes it as an “admonition to those who trusted in ‘heroes’ and leaders to guard the world’s fate.” This particular political pessimism springs from the era of Reagan and Thatcher, the disillusionment of radical politics in the 80s.

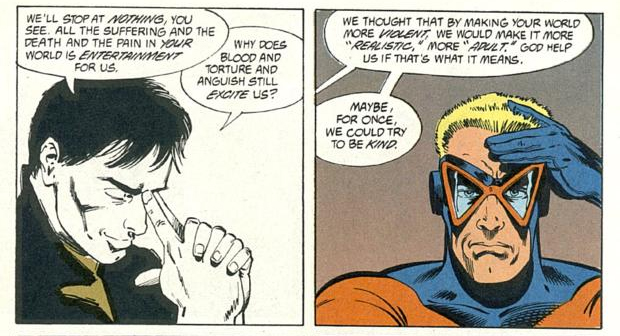

This kind of deconstruction, however, need not be a repudiation of the medium from which it springs, or a wholesale denouncement of the possibility embodied by superheroes. The ending of the series might gesture toward this, with the massive destruction by Adrian Veidt perpetuated with the goal of creating a new unity. The divided, gritty world of Watchmen is no more sustainable than the pure idealism of Silver Age comics.

Moore has discussed the impact Watchmen had on comics as a whole, such as in an interview with AV Club in 2001.

I think that what a lot of people saw when they read Watchmen was a high degree of violence, a bleaker and more pessimistic political perspective, perhaps a bit more sex, more swearing. And to some degree there has been, in the 15 years since Watchmen, an awful lot of the comics field devoted to these very grim, pessimistic, nasty, violent stories which kind of use Watchmen to validate what are, in effect, often just some very nasty stories that don’t have a lot to recommend them.

In the same interview, he continues: “The gritty, deconstructivist postmodern superhero comic, as exemplified by Watchmen, also became a genre. It was never meant to. It was meant to be one work on its own.”

Those who followed Moore seem to have taken his deconstruction of the superhero comic at face value, without looking at the nuance underlying it. This is the source of the idea that the idea of the superhero as heroic is somehow outdated or irrelevant, that there’s no such thing as a good person. While flaws are important to the construction of a compelling character, the extreme of grimdark storytelling makes a character out of nothing but flaws: no striving to be better, no room for idealism. The world can only be saved by killing everyone in it. The solitary (invariably male) hero is all.

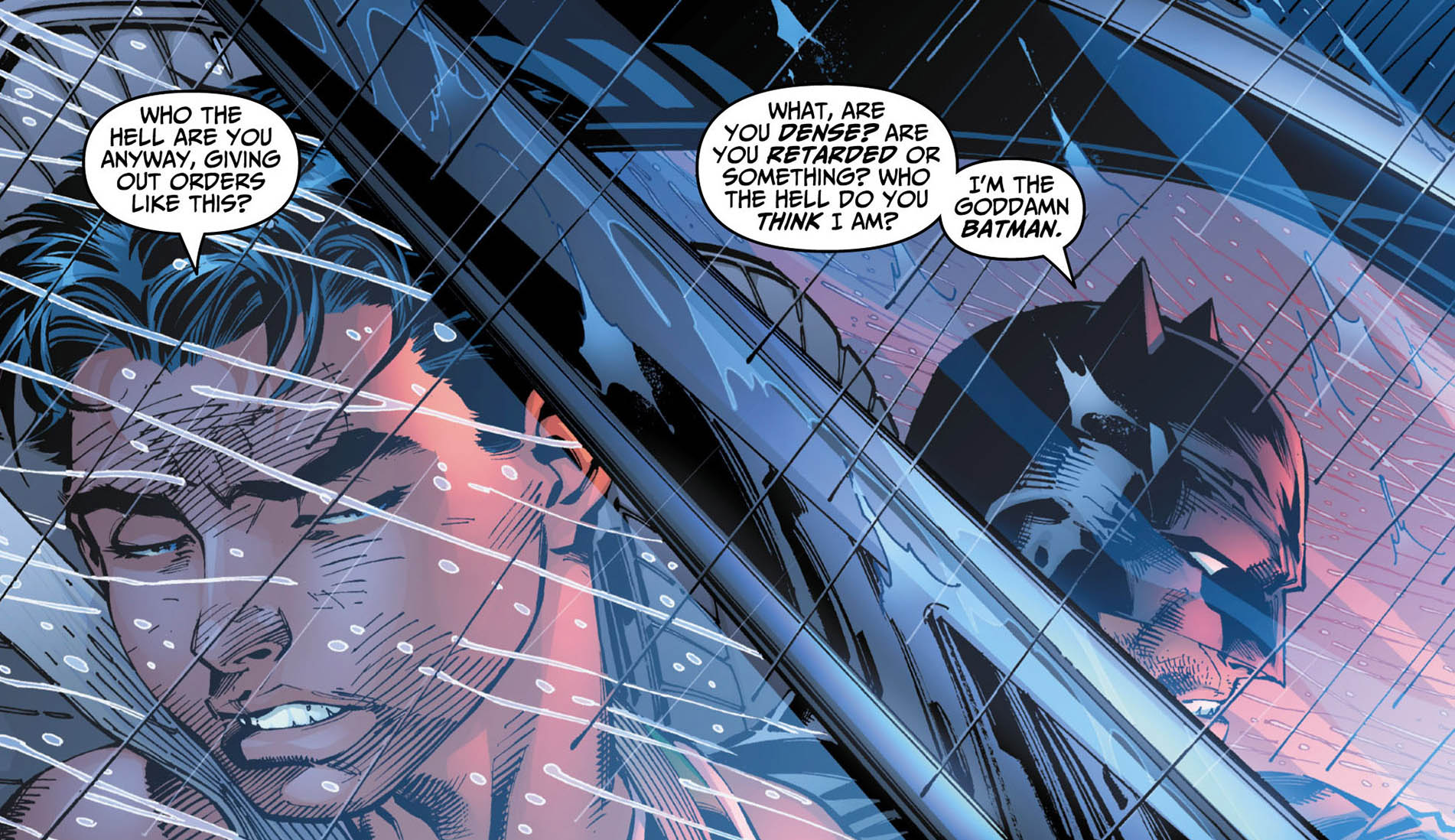

An example of this, almost parodic and now ascended to the status of meme, is Frank Miller’s notorious All Star Batman & Robin. In the comic, Batman is violent and cruel, a sadist who even extends his abuse to innocents, slapping Dick Grayson (the first Robin) across the face and withholding food, telling him to eat rats if he is hungry. The most notorious, and most parodied line is Batman’s response to Dick Grayson’s demand to know who his near kidnapper is. “What are you, dense? Are you retarded or something? Who do you think I am? I’m the goddamn Batman.”

This may be an egregious example, but it is far from the only one of its kind.

The problem with grimdark storytelling is not just a matter of boring homogeneity or the misogyny that often comes along with it – it is the stripping of the possibility of joy and wonder, an excising of the ability of characters to form relationships and interact meaningfully with others. It limits and stifles narratives, locking everything into blacks and grays. This not only creates a world devoid of happiness – it also devalues its tragedies.

Thankfully, comics in recent years have started to turn around, as exemplified by playful titles like Unbeatable Squirrel Girl and Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur that aren’t afraid to use bright colors and exuberant writing. Nothing exemplifies this paradigm shift quite as much as DC’s Rebirth initiative, which foregrounds in its first issue the relationships, familial and romantic, that were lost in the widely derided New 52 reboot. To make the repudiation of the ethos of the New 52 almost anviliciously obvious, the reveal of the villain at the end of issue #1 uses the smiley face splashed with blood: Watchmen’s most iconic image.

Further Reading: When Were Superheroes Grim and Gritty? by Jackson Ayres, On Grittiness and Grimdark by Foz